Mount Madonna School (MMS) offers a robust and thoughtful humanities curriculum. Engaging in independent reading and analyzing full texts begins in third grade. MMS students, particularly in middle and high school, have the opportunity to engage deeply with full-length works of literature, learning not only to read but to think critically, engage in meaningful discussions and develop a strong command of language.

Mount Madonna School (MMS) offers a robust and thoughtful humanities curriculum. Engaging in independent reading and analyzing full texts begins in third grade. MMS students, particularly in middle and high school, have the opportunity to engage deeply with full-length works of literature, learning not only to read but to think critically, engage in meaningful discussions and develop a strong command of language.

While MMS has a rich history of providing a depth-filled, robust humanities curriculum, many schools are struggling to do so.

In Rose Horowitch’s story, “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books” (published in the November issue of The Atlantic), the author describes a concerning trend of students arriving for college unprepared to read books.

“It is not entirely surprising to hear about the challenges students across the country are facing when it comes to reading and literary analysis,” commented Mount Madonna Head of School Ann Goewert. “Digital distractions abound, and the focus on standardized testing often overshadows not only the development of foundational skills but also reading stamina, a love of reading, curiosity and imagination.”

Although Mount Madonna has a long-standing no cell phone policy, for the current school year, administrators decided to collect cell phones in the morning and remove this distraction from the learning environment. Overall, MMS has received positive feedback from the families and the students.

“A focus on comprehensive literacy and analytical skills is truly invaluable for our students in their journey beyond Mount Madonna School,” said Goewert. “It is the hard work and dedication of our talented faculty that support this important work.”

“A focus on comprehensive literacy and analytical skills is truly invaluable for our students in their journey beyond Mount Madonna School,” said Goewert. “It is the hard work and dedication of our talented faculty that support this important work.”

Alumna Tabitha Hardin-Zollo (‘20), currently a graduate student at Columbia University, said the education she received at Mount Madonna School prepared her well for college literacy expectations.

“Humanities at MMS is not just about reading comprehension and regurgitation,” said Hardin-Zollo. “It forces students to analyze and apply multidisciplinary concepts while crafting arguments that are just as engaging as they are compelling. The rigorous humanities courses at MMS prepared me to choose, and excel at, undergraduate and graduate institutions that have analytical writing and self-directed literature research as core components of their curriculums.“

Recently, several Mount Madonna School humanities teachers reflected on the premise put forth in The Atlantic article, their familiarity with curriculum at other educational institutions, and shared comments on the pedagogy informing their own classroom practices, curriculum and understanding of students and their needs.

“An important idea to emerge in the study of the humanities is that to study the world is at the same time to study how we study the world,” said twelfth grade English and humanities teacher Greg Shirley. “By studying how we have sought to understand the world throughout history, we gain insight not just into the world, but into ourselves as well. Additionally, the humanities are an opportunity to understand the significance of STEM disciplines better.

“Studying the humanities requires sustained focus since the ideas studied are found in books, stories, articles and other texts that must be read and interpreted,” he continued. “A challenge in teaching the humanities is to teach students to engage in sustained focus when there are many transient distractions present.

“Studying the humanities requires sustained focus since the ideas studied are found in books, stories, articles and other texts that must be read and interpreted,” he continued. “A challenge in teaching the humanities is to teach students to engage in sustained focus when there are many transient distractions present.

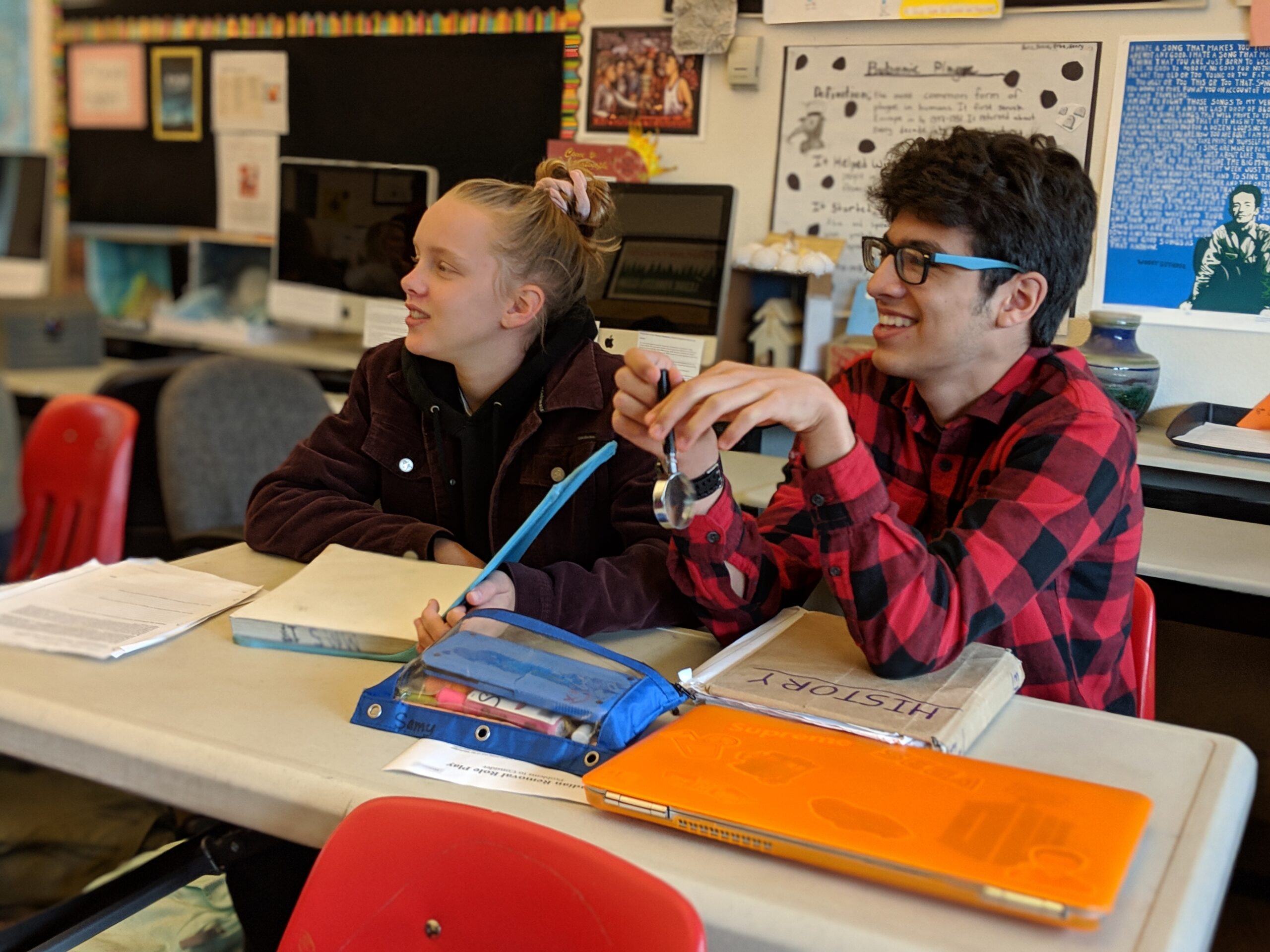

“The MMS cell phone policy removes a major distraction in the classroom and helps to create a space for study,” continued Shirley. “Having students leave their backpacks outside the classroom and bring only their book(s), computer, notepad, and a pen/pencil also reduces distractions. Reading together in class provides an opportunity to model good reading comprehension and interpretation skills and habits. Asking students to take notes and write in-class essays and rough drafts by hand also helps develop their capacity for sustained focus.”

At the elementary school level, third grade is quintessentially understood as when most students pivot from learning to read to reading to learn.

“When we think of how our brains are made, they’re built for stories and narrative,” said Aliya Taylor, MMS third grade English and language arts teacher.

MMS third grade students read a number of full chapter books, including the “Amelia Bedelia” stories by Peggy Parish and Herman Parish, and the “Magic Treehouse” series by Mary Pope Osborne.

“When young readers are immersed in complete texts, as opposed to brief excerpts of only a page or two, they are reading the stories how they were written and taking in dialogue, sentence structure, grammar — even if they don’t realize it,” said Taylor. “The next ‘flip’ is when they move into informational, non-fiction texts.

“When young readers are immersed in complete texts, as opposed to brief excerpts of only a page or two, they are reading the stories how they were written and taking in dialogue, sentence structure, grammar — even if they don’t realize it,” said Taylor. “The next ‘flip’ is when they move into informational, non-fiction texts.

“Students begin to learn to identify what type of piece of writing they are reading — narrative, informational, comparative or persuasive — and how to identify the thesis and main points. I don’t think third grade is too young to understand that structure. As students break down text into parts, identifying paragraphs, the introductory sentence, transition sentences, etc, it provides a template for how they understand a work, as well as how they write about it; all skills that they will develop and build on at every subsequent grade level. It provides a framework for how they learn to analyze texts.”

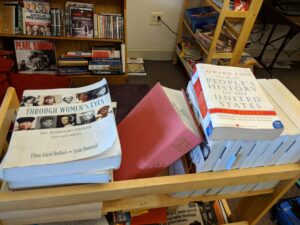

In addition to textbooks for her sixth, seventh and eighth grade history classes, middle school teacher Manjula Stokes curates a list of historical fiction specific to each grade level.

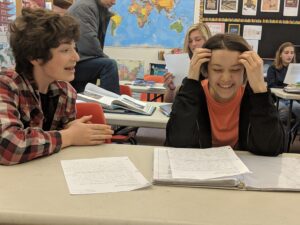

“I want students to engage with material from various perspectives,” said Stokes. “Historical fiction provides students the opportunity to view history as an ‘insider,’ especially when the book is from the point of view of a character their own age. They may see themselves in struggles and triumphs as well as relating to past events.

“For example, in ‘Fever’ by Laurie Halse Anderson, the author writes about the Yellow Fever pandemic,” she continued. “Many students discussed how they related to this event, because it was similar to what they experienced with COVID-19, a significant event in their lifetime. Historical fiction allows readers to immerse themselves in the story and connect on a human level. They develop values and learn what others have gone through.”

This theme continues throughout Mount Madonna’s high school English program in which multiple viewpoints from a variety of texts are incorporated into the curriculum.

This theme continues throughout Mount Madonna’s high school English program in which multiple viewpoints from a variety of texts are incorporated into the curriculum.

“Nigerian author Chimamanda Adichie writes, ‘Many stories matter,’ said high school English teacher Sangita Diaz-Houston. “Reading together, engaging with poetry and literature, and respectfully debating with the authors and each other are all ways that students can broaden their own understanding. The more perspectives that students are exposed to, the less likely they are to seek a polarized, one-dimensional position on a given topic.

“Although this approach to learning is not new, social media has changed how students are socialized to engage,” she continued. “On screens, we don’t have to wait for others to speak before expressing ourselves. If we don’t like content, we can swipe or disengage with no consequences. In addition, algorithms present a reality where we can expect to encounter people with the same opinions and interests. This stunts our ability to listen and understand differing viewpoints.

“In the classroom, students have to realign their expectations of engaging with each other and with the written word,” said Diaz-Houston. “Meaningful learning often happens through face-to-face interactions with each other. In this context, students cannot dismiss an opinion that they do not agree with, but are required to engage with civility and an open mind. In order to counteract the polarization that we see in our society, we must give students the skills for civil discourse.

“For me as a teacher, this boils down to clear expectations, trusting relationships and the willingness to listen,” continued Diaz-Houston. “The culture of Mount Madonna School emphasizes recognizing each student as a whole person and building positive relationships between students, faculty and staff. This aids our work to create an environment where we can engage with each other in respectful dialogue.”

“For me as a teacher, this boils down to clear expectations, trusting relationships and the willingness to listen,” continued Diaz-Houston. “The culture of Mount Madonna School emphasizes recognizing each student as a whole person and building positive relationships between students, faculty and staff. This aids our work to create an environment where we can engage with each other in respectful dialogue.”

MMS high school students read and analyze four to six complete works in English class each school year. This year, assigned works include: “The Odyssey” by Home (translated by Emily Wilson), “Sita’s Ramayana” by Samhita Arni, “Feed” by M.T. Anderson, “Born A Crime,” by Trevor Noah, “The Hate U Give,” by Angie Thomas, “Bless Me, Ultima,” by Rudolfo Anaya, “Braiding Sweetgrass” by Robin Wall Kimmerer and “Othello” by William Shakespeare. Additional selections are, “Jane Eyre” by Charlotte Bronte, “The Importance of Being Earnest” by Oscar Wilde, “Candide” by Voltaire, “The Stranger” by Albert Camus, “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” by Tom Stoppard, “Hamlet” by William Shakespeare and “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” by Maya Angelou.

“I read a lot of books in English class and our class had good discussions, as we debated the author’s meaning of a certain phrase or the relevance and impact of metaphors and character usage,” reflected alumna Kira Kaplan (’21), a senior at Smith College. “I learned how to write critical essays and get my point across clearly, something I think a lot of my peers still have trouble with.

“I also greatly appreciated the variety in texts we surveyed,” she continued. “We weren’t just focused on Shakespeare or fiction. In Values and World Religions classes, I was exposed to philosophers and historians who wrote in what, at the time, seemed to be an entirely different language. It was a whole new style of writing that required in-depth analysis and reflection on each idea that the authors posed. Texts such as these helped to prepare me for the reading that I frequently encounter in my college classes.”

Claire Otterness who teaches seventh and eighth grade English at MMS, says it’s invaluable for students to engage with full-length texts for reasons that go beyond vocabulary building and other language skills.

“Reading full texts encourages students to think more critically through character, thematic and plot analysis, while fostering a deeper comprehension and the ability to draw connections between different ideas and notice how such characters, themes, and plots change and evolve over the course of the text,” said Otterness. “As students discuss these elements in class, they learn to articulate their thoughts and defend their interpretations, honing their analytical skills.

“Reading a variety of full-length texts also helps develop students’ social-emotional skills, such as empathy and compassion,” she continued, “ and allows them to step into the shoes of characters who might be vastly different from themselves. For example, seventh grade students are currently reading ‘Efren Divided’ by Ernesto Cisneros, a novel written from the perspective of a child of immigrants. Supplementing that reading is an assignment where the students write a narrative essay from the perspective of a child of immigrants. Having exposure to the full text, along with a holistic analysis of it, cultivates empathy and broadens their understanding of the world, helping them to relate to others in their communities and beyond.”

“Reading a variety of full-length texts also helps develop students’ social-emotional skills, such as empathy and compassion,” she continued, “ and allows them to step into the shoes of characters who might be vastly different from themselves. For example, seventh grade students are currently reading ‘Efren Divided’ by Ernesto Cisneros, a novel written from the perspective of a child of immigrants. Supplementing that reading is an assignment where the students write a narrative essay from the perspective of a child of immigrants. Having exposure to the full text, along with a holistic analysis of it, cultivates empathy and broadens their understanding of the world, helping them to relate to others in their communities and beyond.”

“Encountering new words in context allows students to understand the nuances of language to help improve their expression,” commented Otterness. “This is essential not only for academic success, but for effective communication and self-expression in all realms of life. Being able to identify key details within a text is helpful for overall comprehension and sharpens analytical functioning. This way students can stay on track with understanding what is going on in the text, increasing fluency in reading. Finally, having the students write comments per assigned section is key for developing their critical thinking skills. This type of engagement allows students to bring their own unique interpretation into play, helping to instill in them the value of their own ideas, and giving them the confidence to engage with and respectfully challenge the ideas of others.”

A capstone in Mount Madonna’s educational catalog is the two-year Values in World Thought course for high school juniors and seniors. During eleventh grade, in addition to reading poetry, short stories and interviews, students read “Just Mercy” by Bryan Stevenson, “Man’s Search For Meaning” by Victor Frankl and “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

The twelfth grade Values class, Self and Society, is actually designated as an English class. Students read a variety of fiction and nonfiction, which explore contemporary moral issues and the construction of moral thinking and systems. Books include “Behind the Beautiful Forevers” by Katherine Boo, “Ethics for the New Millennium” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, “Justice” by Michael Sandel, “Caste” by Isabel Wilkerson and “The Righteous Mind” by Jonathan Haidt.

The twelfth grade Values class, Self and Society, is actually designated as an English class. Students read a variety of fiction and nonfiction, which explore contemporary moral issues and the construction of moral thinking and systems. Books include “Behind the Beautiful Forevers” by Katherine Boo, “Ethics for the New Millennium” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, “Justice” by Michael Sandel, “Caste” by Isabel Wilkerson and “The Righteous Mind” by Jonathan Haidt.

“When designing my curriculum, I wanted to pick books that expose my students to new perspectives and challenge them to read deeply,” commented Shannon Kelly, upper school director and Values in World Thought teacher. “I believe that when done right, analytical reading and writing becomes a conversation between the reader and writer. I teach my students to engage texts with curiosity, much as a detective would. What does the author’s tone and language choice tell us about their thinking? How do we use textual evidence to take our writing beyond opinion to a place where we are wrestling with the text and forming new ideas substantiated by the text?

“The skills we develop through analytical reading and writing are essential,” Kelly continued. “We develop empathy, perspective taking, compassion, logic and curiosity, among other things, through these practices. Humans make sense of the world through storytelling. I think that the desire to make sense of the world and our experience through storytelling is an essential part of humanity.”