In the following article, faculty member Lisa Catterall offers a perspective based on her recent guest teaching experiences in China and her work with STEM and creativity-based curriculum development.

In the following article, faculty member Lisa Catterall offers a perspective based on her recent guest teaching experiences in China and her work with STEM and creativity-based curriculum development.

Over the past year I’ve had the opportunity to work with the Chaoyang District in central Beijing, as well as the Chinese National Science Foundation (NSF) to improve teaching and schools in China’s largest district. Chaoyang has a larger population than Los Angeles. One of the first things I noticed when I deplaned in Beijing was the completely different scale of population. I disembarked into a building that stretches farther than I could see in two directions – all indoors – and walked a corridor with kilometer markers on a long journey to the immigration counter. Then I drove past a never-ending sea of buildings larger than any in America (outside of New York), and I realized that each of the hundreds of thousands of tiny windows contains a family.

Chaoyang District has a teaching institute with a five-year mission to bring week-long trainings by foreign experts to every single teacher and administrator in the area. As the other “experts” in the program all have Ph.Ds, and most have written books and engaged in speaking tours, I often feel out of my league, though fortunate to be invited back periodically and to learn from the other trainers. I am sponsored as a teacher trainer by the American Chinese Cultural Exchange Foundation (ACCEF) and the Chaoyang Institute Internationalization Program.

I was originally selected to participate due to my consulting work with the Center for Research on Creativity (CROC) and the initial course offering was Arts Integration, which is my main research area at WestEd.org.

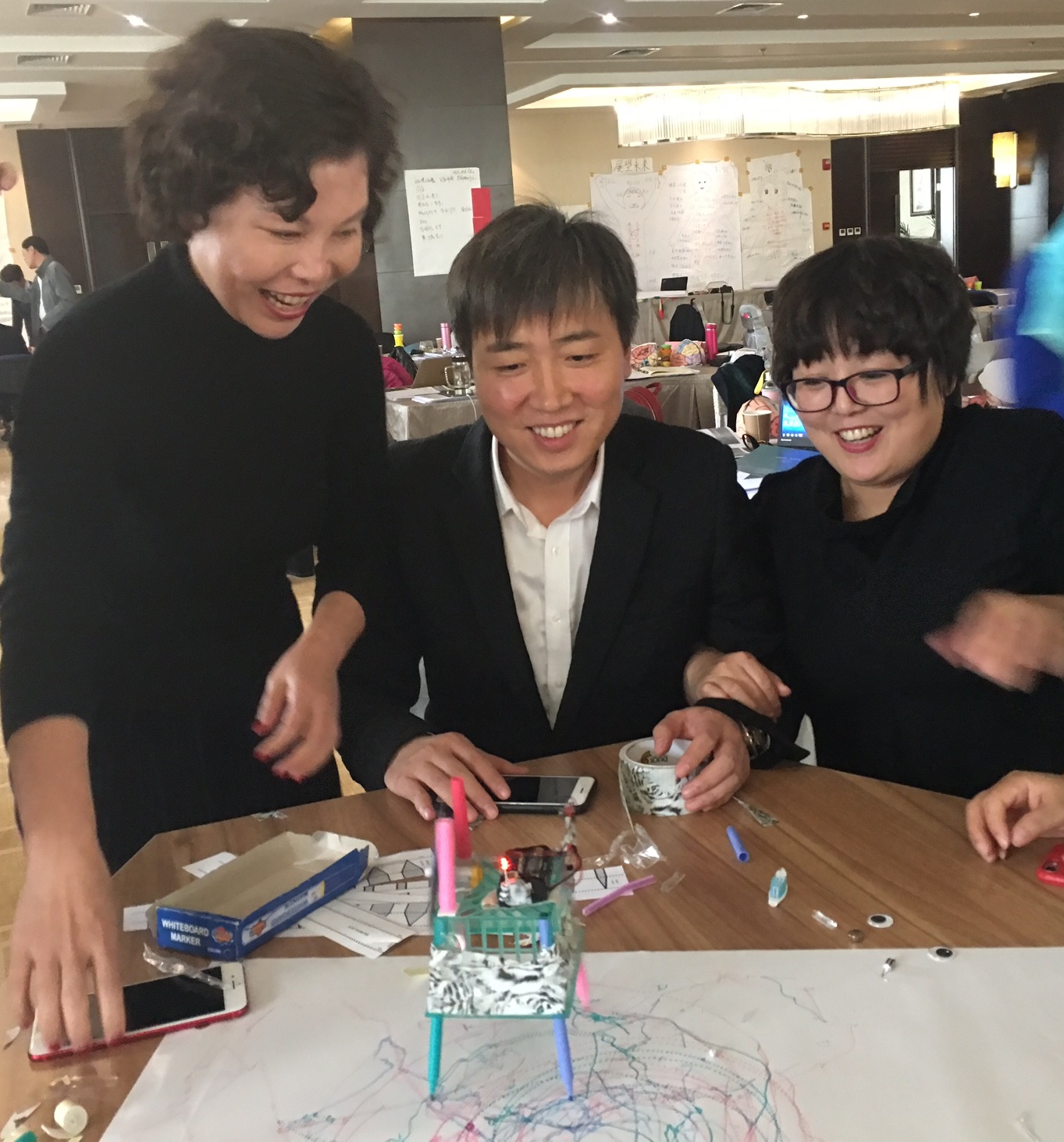

During my most recent trip for the International Maker Education Summit, I co-taught 47 superintendents, principals, and principals-in-training. The trainees included two high secretaries of the Communist party as well as a government observer. I was working with an expert in arts integration, and I wondered how the people gathered in the room might feel about such edgy activities as choreographing dances to explain neurotransmitters, and creating colorful wall art to show the timeline of child development. The head of Chaoyang District visited our class for a presentation on the final day, and I had the chance to ask him what his goals are for the program.

During my most recent trip for the International Maker Education Summit, I co-taught 47 superintendents, principals, and principals-in-training. The trainees included two high secretaries of the Communist party as well as a government observer. I was working with an expert in arts integration, and I wondered how the people gathered in the room might feel about such edgy activities as choreographing dances to explain neurotransmitters, and creating colorful wall art to show the timeline of child development. The head of Chaoyang District visited our class for a presentation on the final day, and I had the chance to ask him what his goals are for the program.

His answer surprised me. The course titles I teach are Neuroscience and Learning, and Curriculum Leadership for Principals. Coming from a background in the American system, I was assuming a high official in a top-down management district would mainly be considering the effect the trainings would have on his “big data,” or test scores.

Instead, he smiled and said, “I want you to make them happy.” Shocked, I asked him to elaborate. He explained that schools overflowing with happiness and love were clearly the only ones functioning in the world. He had just visited Finland for three weeks to observe what is generally accepted to be the world’s finest education system. “If you send them back to their schools happy, and understanding the value of personal growth, they will encourage it in their staff, and it will begin to happen for the students. I want them to be happy, and to grow from within while they are with you.”

I know for a fact that in Finland they have extended teacher training to eight years, and teachers are paid more than doctors. In China, and in our area, teacher pay is such that it is difficult to pay for housing. Finland also whittled down their standards from large books to about five bullet-points per subject, per grade, in order to give their highly trained and well-paid teachers maximum freedom to be creative. I am sure that anything I can do in a week could not have as strong an impact.

After our students’ presentation, which included theatrical tableaux, homemade robots, and artistic video sprinkled among personal reflections, the head gave a passionate speech. He shook his finger at his leaders and said, “We have all spent too long making learning miserable. Learning is human. Learning should be joyful. When schools are working, every member of the community is happy, and the students and teachers are joyful.”

After our students’ presentation, which included theatrical tableaux, homemade robots, and artistic video sprinkled among personal reflections, the head gave a passionate speech. He shook his finger at his leaders and said, “We have all spent too long making learning miserable. Learning is human. Learning should be joyful. When schools are working, every member of the community is happy, and the students and teachers are joyful.”

I began to understand why my drive to take risks to change the paradigms in educational systems is working well in China. I walk through schools there and notice that while the classrooms are full of expensive technology, and the labs and studios are stuffed with the best resources in the world, the desks are still in rows. The children still march. Lessons are still memorized and recited. The Chinese have long produced the world’s best population of followers; now they are attempting to usher-in an era of leaders.

Last spring, when I arrived to teach my first class in China, my upcoming book and the STEAM/makers consulting I’ve done got the attention of NSF, and they approached me about consulting as an expert in STEAM/maker education. The NSF has an interest in funding a large makers curriculum project, which MMS students could potentially participate in here on campus. At the first meeting I had with them, the head of the NSF there summarized what they wanted me to do. He said, “Everything in the world now says ‘Made in China.’ We want it to say ‘Invented in China.’ You will help us get there.”

I returned a week later, for a day, to give a half-hour speech. I did not know what to expect, and was surprised to find a room set-up very much like a TED talk, with technology I’d never seen. The venue was full of vendors of expensive robots. Surprisingly, one of the robots being sold matched exactly one in my slide show! The slide includes the robot pictured alongside a messy, creative, solar-powered work of kinetic art made by an MMS student as an entry into our annual solar race, and reads “Kits and Single Answers vs. Infinite Possibilities: Creativity in the Classroom.” Our little solar car, from our little program, was fifty feet tall, standing high above the robot vendors.

I returned a week later, for a day, to give a half-hour speech. I did not know what to expect, and was surprised to find a room set-up very much like a TED talk, with technology I’d never seen. The venue was full of vendors of expensive robots. Surprisingly, one of the robots being sold matched exactly one in my slide show! The slide includes the robot pictured alongside a messy, creative, solar-powered work of kinetic art made by an MMS student as an entry into our annual solar race, and reads “Kits and Single Answers vs. Infinite Possibilities: Creativity in the Classroom.” Our little solar car, from our little program, was fifty feet tall, standing high above the robot vendors.

Photographs of from our MMS makers’ program and our students’ makers projects are sprinkled throughout my TED-type talks for my keynote speeches at Chinese makers’ conventions. Their growing edge is around having the kids actually make stuff, rather than just play with toys that are marketed as “makers” or “STEAM.” In fact it is the same growing edge a lot of programs here have (if you ask a student from another local independent school what they do in STEAM, they’ll say they just “play with the Makey Makey,” which is an expensive toy). Our kids’ projects are prime examples of open-ended creativity. On this last trip I met a couple from San Francisco who has lived in China for five years, and they’ve been pioneers in bringing actual open-ended makers’ curriculum there, but that’s the only time I’ve seen it.

I’m really not sure how to gauge reactions of the Chinese participants as I do not speak Mandarin. Recently, however, I was invited back for a three-day speaking tour, as well as a meeting to talk about launching a curriculum in China. Just like the buildings, the scale is something we’re just not accustomed to here in the United States. The districts serve millions and individual schools serve thousands each. It’s humbling and fulfilling to know the work we started here in our own small makers’ factory could expand the minds of so many students.

I hope to be able to continue offering teacher and principal training courses in the summer and perhaps one additional time per year. I also want to keep helping to get the word out about this huge makers’ curriculum project. That project, if it gets funded, is a real goal for me. It would throw thousands of dollars behind writing-up and publishing The Factory (MMS’ makers’ lab) curriculum we’ve already developed (about thirty projects), and would fund development of sixty more projects as well as sponsor training courses for the curriculum in Beijing and the United States. The curriculum would be published in the U.S. and China, and the intellectual rights would be shared between me, MMS, the ACCEF, CROC, and the NSF. Right now the U. S. National Science Teachers Association also wants the curriculum, but they are asking for exclusive rights, and it can reach many more people in the way that the Chinese propose publishing it.

I hope to be able to continue offering teacher and principal training courses in the summer and perhaps one additional time per year. I also want to keep helping to get the word out about this huge makers’ curriculum project. That project, if it gets funded, is a real goal for me. It would throw thousands of dollars behind writing-up and publishing The Factory (MMS’ makers’ lab) curriculum we’ve already developed (about thirty projects), and would fund development of sixty more projects as well as sponsor training courses for the curriculum in Beijing and the United States. The curriculum would be published in the U.S. and China, and the intellectual rights would be shared between me, MMS, the ACCEF, CROC, and the NSF. Right now the U. S. National Science Teachers Association also wants the curriculum, but they are asking for exclusive rights, and it can reach many more people in the way that the Chinese propose publishing it.

Truthfully, a project of that scope has not been completed in the U.S., either, so it’s a true international collaboration, if it gets funded. They have a lot of money there so I’m hopeful. Also, the teacher trainer I work with, Dr. Sherry Kerr, is a scholar at the Center for Research on Creativity. The other goal is that she and I are going to take the innovative Creativity Ed training we do for principals and teachers in China, and work on transporting them to the United States’ rural south and the “rust belt,” where more innovative education is really needed.

By Lisa Catterall

####

Contact: Leigh Ann Clifton, Director of Marketing & Communications,